“Action research is rather simple,” was what one teacher said after learning about how action research could be applied to her own classroom in our workshop earlier this week. For most educators—scratch that—for most people, action research is daunting. It’s this esoteric ‘thing’ of which only those with advanced degrees are capable. However, action research is much more ordinary than that. Look around you: that stranger next to you likely practices some aspects of action research in his or her everyday life without even knowing about it.

Of course, one person’s opinion on action research isn’t representative of the general public’s view on it, and action research does take practice.

But action research is doable and design thinking can help teachers use it for themselves.

Richard Sagor, a respected researcher on the topic, said that action research “is a disciplined process of inquiry conducted by and for those taking the action. The primary reason for engaging in action research is to assist the ‘actor in improving and/or refining his or her actions’.” In other words, it’s very human-centered: a key characteristic of design thinking.

When we prepared for our workshop in the National Digital Educators Society (NDES) Summit, we wondered how we could package action research to teachers in a way that would motivate them to use it in their own classrooms. Taking account the added expectations of our audience—they were educators seeking to better implement digital technology in their classrooms—we had a tricky task at hand: we had to clearly define the intersection of action research, design thinking, and digital technology all in one take.

With many different applications available on the web today, integrating digital technology to action research is easy. For our workshop, we used padlet.com to pool answers from our clients. We asked them to comment on what they thought were the distinct challenges, definitions, and experiences of action research. Then, their responses were organized in a shared word cloud. This allowed us to streamline the inquiry process of action research.

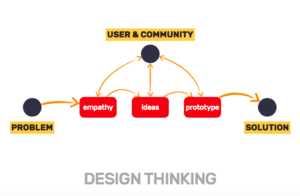

Our next task was to show the connection between design thinking and action research. Based on Sagor’s definition, action research is a heuristic approach: the actor is always “improving and/or refining his or her actions.” It’s a moment-by-moment theorizing of actions, where the researcher relies on a model of continuous action and reflection. Looking at design thinking’s four tenets,

1. empathy for users,

2. collaborative ideas,

3. rapid prototyping,

4. and immediate feedback,

it’s also oriented towards making things easier for the actor through continuous action and reflection or, in design thinking terms, prototyping and feedback. We wanted our audience to understand that action research and design thinking were there to make their lives easier and that design thinking packaged action research in a clear and systematic way.

To do so, we introduced them to a design thinking rush where they needed to invent a ‘memory enhancer’ for a group member they just met. At first, they were told to sketch a ‘memory enhancer’ that they thought would help their partner. After, they would share with each other their designs. Often, the conversation would reveal the assumptions of the designer. They would build a ‘memory enhancer’ that they thought would work best for them, instead of a ‘memory enhancer’ that would work best for their partners. This is because people typically see problem solving as two-step and linear: there’s a problem which has a solution. The middle part of this problem solving sandwich is the designer’s own assumptions, which unfortunately doesn’t always meet his or her client’s needs.

In contrast, design thinking attempts to replace the designer’s assumptions with the actual needs of the client. Since the designer’s assumptions are accounted for, problem solving becomes a conversation between designer and client.

Here, the conversation is grounded by empathy, opening up room for diverse ideas and constant prototyping and feedback to take up space between both parties.

After learning about this, our audience created ‘memory enhancers’ which made the lives of their partners easier. Some came up with sorting trays for the overloaded teacher, while others created high-tech watches for the on-the-go administrator. Ultimately, they learned to place the needs of their partners above their own assumptions, as well as carefully polish their partners’ needs through constant prototyping and feedback until both designer and client were happy with the solution they came up with together. And that’s how digital technology, action research, and design thinking intersect; they collaborate with each other to make the lives of everyone involved easier.